By Akin A. Ajose-Adeogun

President Houphouet-Boigny of the Ivory Coast was more astute than the leaders of the non-Igbo South and Central Nigeria in 1967, the critical juncture in post-colonial Nigerian history when the power of the Fulani ethnic nationality over the Nigerian state was entrenched.

President Houphouet-Boigny of the Ivory Coast was more astute than the leaders of the non-Igbo South and Central Nigeria in 1967, the critical juncture in post-colonial Nigerian history when the power of the Fulani ethnic nationality over the Nigerian state was entrenched.

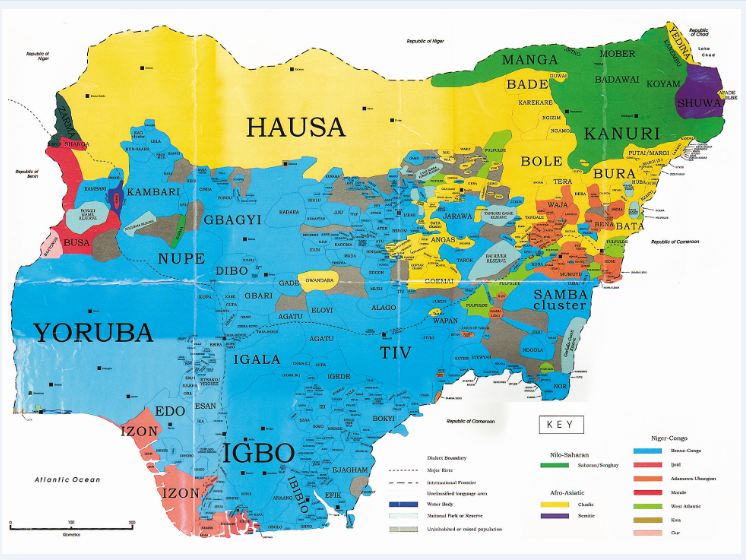

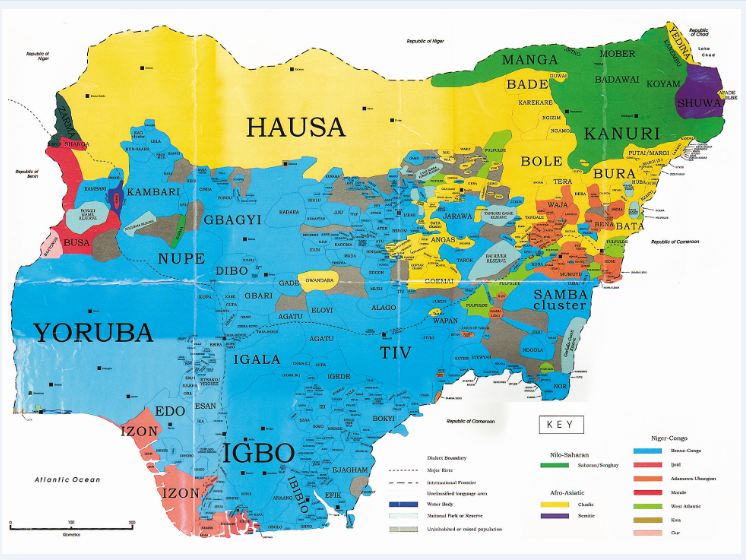

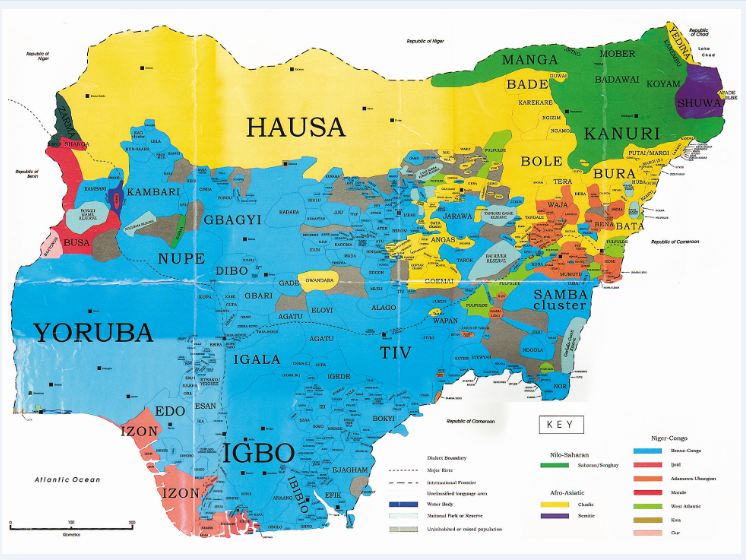

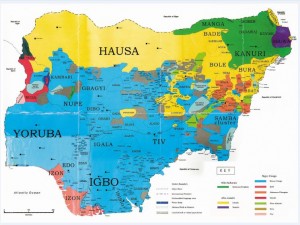

We have suffered for fifty-one years now, the consequences of our leaders’ naivety and blunders in not holding the FGN to its word on the Aburi Agreement that had transformed Nigeria into a confederation, which is the only workable structure for a country that is an ill-assorted ragbag of mutually hostile ethnic groups and conflicting ideologies.

I understand the fears, at the time, of the federal bureaucrats from the minority ethnic nationalities – M.A. Ejueyitchie, M.A. Tokunbo, Allison Ayida, Edwin Ogbu, Abdul Aziz Atta, etc. – who had advised Gowon to unilaterally revise the Aburi Agreement [by introducing ss.70 and 71, which reasserted the power of the FGN over the regions, thus abrogating the confederal nature of Nigeria agreed at Aburi]. But could their genuine fears of domination by the majority ethnic nationalities in the regions not have been simply addressed by arguing for the creation of more states – as, in fact, occurred later on 27 May 1967?

What we appear to be witnessing now is the denouement Houphouet-Boigny had feared : the southward encroachment of West Africa’s Islamic Sahelian belt, which he felt that the “able and intelligent Igbo had an important part to play in preventing.” See Michael Gould, The Biafran War : The Struggle for Modern Nigeria (London : I.B. Tauris and Co., 2013)

According to I. Nolte in his book, Awolowo and the Making of Remo (Edinburgh University Press; 2009), even Awolowo’s most ardent supporters in his Remo Division were baffled by his decision to support the FGN, under “which they had suffered and sacrificed so much during the Balewa regime.” Apparently, it took Awolowo a year to come around to supporting the Gowon government. The creation of the twelve-state structure on 27 May 1967 by Gowon was what won both Awolowo’s and the Eastern ethnic minorities’ support. They wrongly assumed that this move had created a level playing field and weakened the Islamic North’s political stranglehold on the country.

Another vitally important information that emerged in Michael Gould’s book – from interviews with General Adebayo – was that the “North was chronically insolvent and could not have fought the war without the financially buoyant Western State’s financial support.” The excessive taxation burden was what later on triggered off the Agbekoya Revolt of 1969.

According to Dr Michael Gould, the British Foreign Office documents quoted in the book stated that the Northern emirs and political leaders, like Inua Wada, had demanded, in November 1966, that Gowon step down for Murtala Mohammed. Gowon refused, with the support of the Christian Middle Belt soldiers who then prevailed in the infantry (the Tiv, comprising 20%, were the largest ethnic group in the Army. Followed by the Bachama). Outgunned, the Islamic North backed down. But Gowon’s position was very precarious until he obtained the support of Adebayo, Ejoor, and, above all, Awolowo, who brought popular Yoruba support.

Houphouet-Boigny was an extremely astute leader who was highly regarded across the French-speaking world.

At a time that Nigerian leaders saw their problems in a narrower sense of a misunderstanding among ethnic groups in the country, Houphouet-Boigny saw it as a struggle between two rival systems – Islam and Christianity – that has now, historically, lasted for some fourteen centuries. He had seen this as an emerging continental or global problem. And the Ivorian crisis and civil war was about maintaining the Ivorian identity in the face of Muslim migration from the Sahel. We see the same problem today in the Western world, Kenya, Myanmar (Burma), Russia’s Caucasus region, Ethiopian Eritrea, Indian Kashmir, Chinese Sinkiang, and Yugoslav Kosovo, etc.

It was on this basis that Ivory Coast supported Biafra and influenced France and Gabon into doing the same.

The minority ethnic groups and the Yoruba who had both inadvertently helped the Islamic North to entrench a hegemony during the so-called war of Nigerian unity now seek our former decentralised pre-1966 federalism as a minimum demand, as they increasingly feel the lash of the Islamic North’s political stranglehold.

In conclusion, I have to concede that the non-Igbo South and Central Nigeria committed an epic historical blunder.

The Igbo, at a cost of thousands of dead in the pogroms of May and September to October 1966, purchased a confederal system of government for Nigeria. This system of government was, and still is, the most workable one for Nigeria. Unfortunately the rest of the country did not realise it at the time. An incongruous and unholy alliance was cobbled up to fight for a non-existent unity, as events of the last fifty-one years have indubitably made clear.

That so-called war of Nigerian unity resulted in a military victory for the Islamic North, but a moral victory for the Igbo. Ironically, with the benefit of hindsight today, it is the non-Igbo South and Central Nigeria that suffered the greatest defeat. In addition to sustaining a massive moral defeat, both regions also sustained a massive political defeat. Consequently, I do not know whether it is the non-Igbo South and Central Nigeria that should commiserate with the Igbo for the massive loss of lives, or whether it is the Igbo that should commiserate with the non-Igbo South and Central Nigeria for the loss of their souls and possibly an even greater loss of lives in the future to correct a mistake that could probably have been avoided at small cost in 1967. I’m inclined towards the latter position as we approach another critical juncture in our history.